China’s great game in the Middle East

Summary

- China has significantly increased its economic, political, and – to a lesser extent – security footprint in the Middle East in the past decade, becoming the biggest trade partner and external investor for many countries in the region.

- China still has a limited appetite for challenging the US-led security architecture in the Middle East or playing a significant role in regional politics.

- Yet the country’s growing economic presence is likely to pull it into wider engagement with the region in ways that could significantly affect European interests.

- Europeans should monitor China’s growing influence on regional stability and political dynamics, especially in relation to sensitive issues such as surveillance technology and arms sales.

- Europeans should increase their engagement with China in the Middle East, aiming to refocus its economic role on constructive initiatives.

Introduction

China’s evolving role in the Middle East

Camille Lons (project editor)

China has become an increasingly significant player in the Middle East in the past decade. While it is still a relative newcomer to the region and is extremely cautious in its approach to local political and security challenges, the country has been forced to increase its engagement with the Middle East due to its growing economic presence there. At a moment when the United States’ long-standing dominance over the region shows signs of decline, European policymakers are increasingly debating the future of the Middle Eastern security architecture – and China’s potential role within that structure. However, many policymakers have little knowledge of China’s position and objectives in the Middle East, or of the ways in which these factors could affect regional stability and political dynamics in the medium to long term. Given that China’s rise has led to intensifying geopolitical competition in Europe’s neighbourhood, European policymakers should begin to factor the country into their thinking about the Middle East. This series of essays addresses how they can do so by bringing together Chinese, Middle Eastern, and Western perspectives on China’s evolving role in the region.

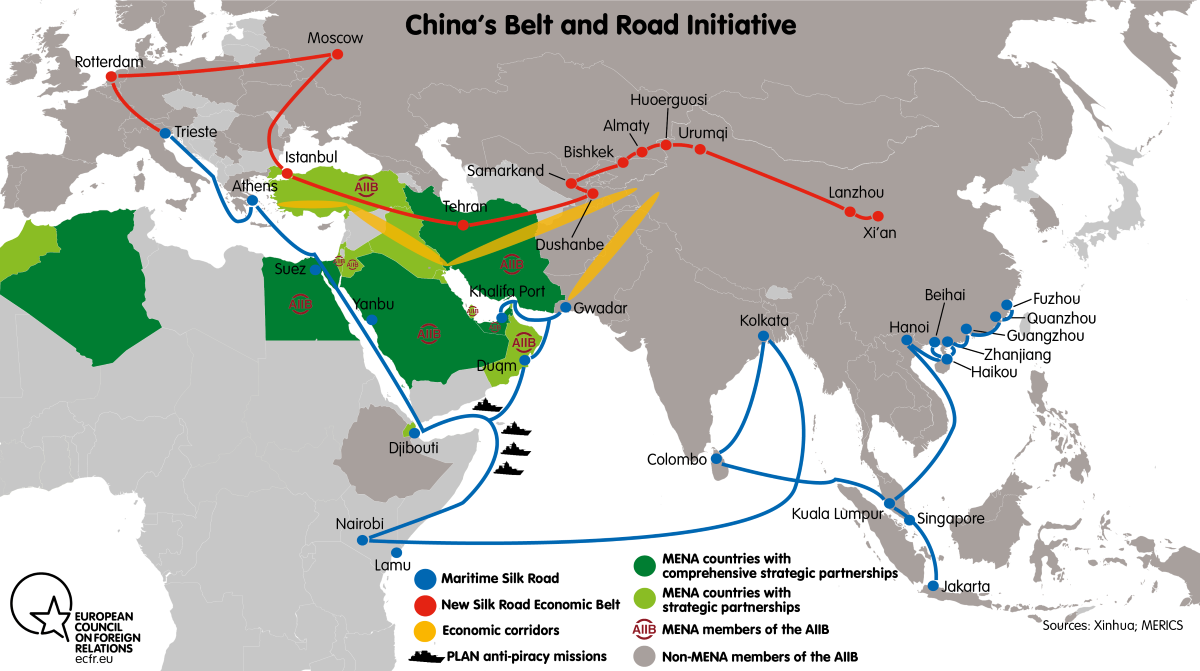

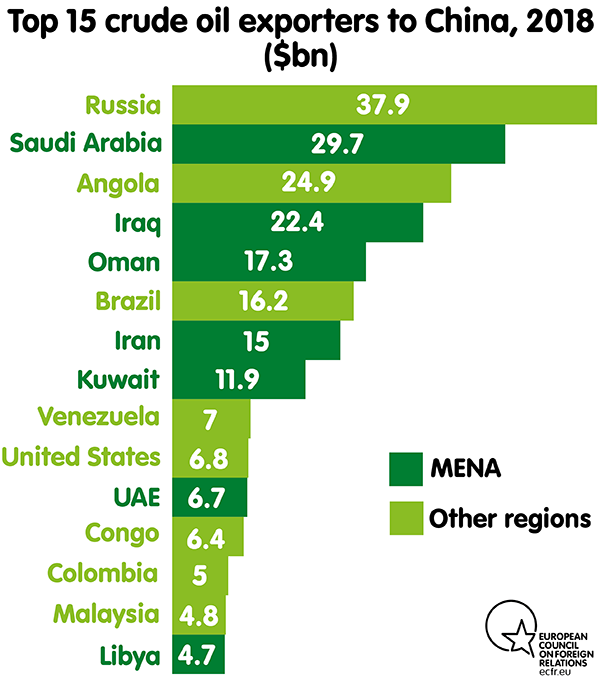

China’s relationship with the Middle East revolves around energy demand and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013. In 2015 China officially became the biggest global importer of crude oil, with almost half of its supply coming from the Middle East. As a strategically important crossroads for trade routes and sea lanes linking Asia to Europe and Africa, the Middle East is important to the future of the BRI – which is designed to place China at the centre of global trade networks. For the moment, China’s relationship with the region focuses on Gulf states, due to their predominant role in energy markets.

As Jonathan Fulton argues, the centrality of economic cooperation and development to China’s engagement with Middle Eastern countries is reflected in two key Chinese government documents, the 2016 “Arab Policy Paper” and the 2015 “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road”. The cooperation framework outlined in these documents focuses on energy, infrastructure construction, trade, and investment in the Middle East. They barely mention security cooperation – in line with Beijing’s narrative that its involvement in the region does not advance its geopolitical goals. Beijing is careful to avoid replicating what it sees as Western intervention and puts forward a narrative of neutral engagement with all countries – including those that are at odds with each other – on the basis of mutually beneficial agreements. As Degang Sun explains, China has a vision of a multipolar order in the Middle East based on non-interference in, and partnerships with, other states – one in which the country will promote stability through “developmental peace” rather than the Western notion of “democratic peace”.

However, Beijing will likely struggle to maintain its neutral narrative as Chinese interests in the volatile region grow. This will be especially true if the US speeds up its apparent withdrawal from the Middle East, a trend that is likely to force China to protect these interests itself. China may not want to strengthen its political and security presence in the region – but it may feel that it has no choice in the matter. Meanwhile, China’s deepening engagement with countries on both sides of fierce rivalries could drag it into disputes unrelated to its core objectives. While it is apparently happy to maintain a more distant role for the moment, China is already showing initial – albeit still small – signs of deepening political and security involvement in the Middle East. It remains to be seen how far the country will take this, and to what end goal.

From economic interests to political and security engagement?

To date, China has concluded partnerships agreements with 15 Middle Eastern countries. It participates in anti-piracy and maritime security missions in the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Aden, and has conducted large-scale operations to rescue its nationals from Libya in 2011 and Yemen in 2015. It has increased its mediation efforts in crises such as those in Syria and Yemen – albeit cautiously so; was instrumental in persuading Tehran to sign the Iran nuclear deal; and appointed two special envoys to Middle Eastern countries in conflict. Moreover, China’s establishment of its first overseas military base, in Djibouti, as well as the probable militarisation of the Pakistani port of Gwadar, contributes to the growth of the country’s military presence near crucial maritime chokepoints the Strait of Hormuz and Bab el-Mandeb. Finally, China has supplied arms to several Middle Eastern countries, albeit on a small scale.

But Beijing has been extremely careful not to become too involved, still believing that the US can take responsibility for managing security in the region. China has played next to no role in easing geopolitical tension in the Middle East, as indicated by the distance its political representatives maintain from major conflicts there. While China has worked with Russia on the UN Security Council to protect the Syrian regime, this stems from its desire to adhere to the principle of non-interference rather than its direct interests in the Syrian conflict.

Given the recent series of incidents in the Strait of Hormuz that increased tension between Iran and its geopolitical opponents, China could be forced to take on a greater security role to protect the freedom of navigation crucial to its energy security. Beijing has kept to a very cautious line following the recent incidents, showing that it is not ready yet to step in significantly. However, a few announcements have marked a departure from this traditional rhetoric. The Chinese ambassador to the United Arab Emirates announced in August 2019 that China might participate in maritime security operations in the strait. The following month, Iranian sources declared that China would be involved in a joint naval drill with Iran and Russia in the Sea of Oman and the northern Indian Ocean. Beijing has not confirmed these declarations. It seems that China will most likely continue its anti-piracy and peacekeeping operations as usual – but these announcements are striking in the sense that they would have been unthinkable only a few years ago.

China appears to be in learning mode in the Middle East. Yet while the region is still relatively peripheral to its foreign policy priorities, there is a widening debate within China about whether greater involvement is necessary to protect Chinese economic interests. An increasing number of Chinese experts argue that their country should shed its image as a free-rider and increase its military presence in the region.

Beijing is also motivated to do so by its desire to challenge US dominance in the Middle East and other regions – as Degang writes. In this respect, the BRI not only promotes global trade and connectivity but also creates an economic system outside Washington’s control.

Nonetheless, for the moment, the US remains the indispensable power in the Middle East – as Fulton contends. This is why China has been careful not to antagonise the Americans on sensitive issues such as Iran. While it has criticised China for being a free-rider in the region, the US would most likely oppose a greater Chinese military presence in the area.

Middle Eastern countries face a similar dilemma. China’s capacity to invest, build infrastructure, and provide public services in developing countries has drawn significant attention from Middle Eastern states and heightened their expectations. For example, Gulf countries have made great efforts to become involved in the BRI and attract Chinese businesses. As Naser Al-Tamimi contends, many of these states perceive China as a useful tool in their strategies to diversify not just economically but also politically at a moment of apparent US retrenchment. Washington’s reaction to recent Iranian attacks in the Gulf – particularly its unwillingness to respond with force – has undermined Arab monarchies’ confidence in the US security guarantee. This has pushed them to seek alternative partners, including China, as part of a hedging strategy.

However, as Tamimi points out, Middle Eastern states are also aware of China’s limitations as a security provider and are, therefore, carefully managing their relationships with the US. For instance, after the US expressed alarm about the possible security consequences of increased technological cooperation between Israel and China, some Israeli companies reportedly drew back from deals with Chinese firms.

Although many Middle Eastern countries support the principle of non-interference and condemn Western intervention in the region, this principle is likely to become a major weakness for China in the near future. China’s opportunistic approach and lack of interest in the region’s politics makes Middle Eastern countries wary about its real value as a partner. For now, China seems content with its relatively passive role.

Consequences for European interests

There are several areas in which China’s engagement with the Middle East will likely have important consequences for European economic and security interests in the medium and long term. By providing a model of non-democratic development and economic engagement with the region, China is slowly establishing itself as a competitor to Western influence in the Middle East. Amid severe regional turmoil, it is important for Europeans to acknowledge this shift, monitor the evolution of China’s economic and security presence there, and find new ways to engage with the country on Middle Eastern affairs. Doing so will help them persuade Beijing to support a stable multilateral framework that protects European interests.

Even if China remains cautious in its political and security involvement in the Middle East, the country’s economic presence there is likely to have important ramifications for Europeans. China is emerging as a crucial development actor in the region, through both direct investment and development support. Its economic importance to the region has the potential to outweigh that of the US and Europe. Middle Eastern countries – particularly those affected by conflict – will need Chinese money to develop critical infrastructure, and such assistance could have far-reaching consequences for them.

China’s standards on the viability of development projects and the conditions attached to them – in relation to good governance, economic infrastructure, the rule of law, and respect for human rights – differ to those of the West. As Degang states, China believes that economic development and the provision of public goods are important to peace and stability but that democratic reforms are not. In this approach, development projects that focus on resource extraction risk reinforcing authoritarian regimes, clientelist networks, and social inequality – with long-term consequences for the political and economic stability of the countries involved.

The Chinese model of authoritarian capitalism already fascinates many Middle Eastern regimes, which see cooperation with China as a means to resist Western pressure to pursue governance reforms and human rights accountability in return for development aid and investment. China’s exports of goods such as advanced surveillance technology could also reinforce authoritarian regimes in the Middle East.

There are many unknown elements in the potential security consequences of Middle Eastern countries’ acquisition of 5G networks and Chinese technology more broadly. With the US having already raised its concerns on this front, Europeans should follow the issue closely in the coming years.

In this context, Europeans can do more to refocus China’s economic role on constructive efforts. For example, several European development agencies are already experimenting with cooperation with China in African countries. The extension of these partnerships to the Middle East could help Europeans understand Chinese developmental practices and promote European governance standards. Moreover, Europeans could provide Chinese actors with the know-how, experience, and networks they seek in the region in return for economic support. If the sides develop a constructive relationship in this way, China could support European stability initiatives in the Middle East. Such cooperation would also provide an opportunity to shape China’s political engagement with the region. Even if China prioritises economic development above political reform, Europeans should not see this as a zero-sum competition.

On a broader political level, China’s limited involvement in the Middle East has been driven by a desire to project an image of itself as a new global power. This has led to unrealistic expectations about the country’s influence in the region, providing Beijing with symbolic power that does not always reflect its real capacities and ambitions.

Middle Eastern states have capitalised on this, using China as a bargaining chip in their interactions with the US and Europe. For instance, earlier this year – only a few months after the killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi – Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman appeared to use his tour of Asia to affect debates in the US and European countries on arms sales to his country. Rather than only seeking to diversify Saudi partnerships with Asian powers, he aimed to issue a strong response to his Western critics. In a similar vein, Gulf countries’ purchases of Chinese military drones have pushed the US to lower its threshold for selling controlled weaponry of this kind.

European countries should not overestimate China’s political influence in the Middle East either. Countries in the region – especially those at odds with the US, such as Iran and Syria – tend to exaggerate their ties with China to ease their isolation. China is not quite as important to the Middle East as it can sometimes seem to be.

Many of the projects and investments China announced within the framework of the BRI have been abandoned or heavily delayed. Meanwhile, in areas such as arms sales, Chinese firms are far from being credible alternatives to Western suppliers.

Therefore, Europeans should recognise the value of their own engagement with regional actors. China – much like Russia, and even the US under President Trump – still falls short of Middle Eastern states’ expectations, thereby giving Europeans space to advance their own positions and interests. As part of this, improved monitoring of China’s regional projects would help Europeans understand how the country is building up its influence in the region. It would also help them avoid becoming too susceptible to their Middle Eastern partners’ bargaining tactics where Chinese leverage is not as strong as it initially seems to be.

European countries should seek new ways to engage with China in the Middle East. In some respects, both sides want the same thing – a stable regional order – and may have room to advance shared policies in pursuit of this goal. European countries will not realistically be able to counter the Chinese economic juggernaut in the region, but they may be able to continue working towards a more stable Middle East while offsetting the authoritarian dimensions of China’s regional expansion. Given China’s desire to keep its distance from Middle Eastern conflicts, Europe can be a useful partner due to its long-standing relationships, personal networks, cultural proximity, and deep understanding of the region that China still lacks. Europeans should think about how to establish a constructive partnership with China – one that ties the country into a cooperative multilateral order as it continues its rise across the Middle East.

China’s challenge to US dominance in the Middle East

Jonathan Fulton

China’s announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 signalled a change in its role in the Middle East. Connecting China to states across Eurasia and the Indian Ocean region, the BRI is the most important foreign policy initiative the country has undertaken since its arrival as a power with global interests. Because the Middle East is crucial to the BRI, China’s approach to the region is becoming more ambitious and complex on economic, diplomatic, and – to a lesser degree – security issues there. This is reflected in two Chinese white papers, “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road” and “China’s Arab Policy Paper”.

“Vision and Actions” says little about the Middle East specifically but announces five cooperation priorities for developing relations with states that participate in the BRI: political coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bonds. The absence of security and military cooperation in “Vision and Actions” supports the Chinese narrative that the BRI is a development-centred initiative rather than part of a geopolitical strategy. Consistent with China’s past approach, these cooperation priorities provide a road map for the development of its relationship with the Middle East in the coming years.

“China’s Arab Policy Paper”, released to coincide with Xi Jinping’s first presidential trip to the Middle East, outlined a Chinese vision for the region in which “China is willing to coordinate development strategies with Arab states, put into play each other’s advantages and potentials, promote international production capacity cooperation and enhance cooperation.” Central to this is the “1+2+3 cooperation pattern”, with “1” representing energy as a core interest; “2” infrastructure construction, as well as trade and investment; and “3” nuclear energy, satellites, and new energy sources. While largely dismissed upon its release as short on specifics and long on platitudes, the paper has, in hindsight, signalled trends in Chinese engagement with Arab states.

Energy at the core

China remains a major buyer of oil and natural gas from Middle Eastern exporters. The Middle East accounts for more than 40 percent of China’s oil imports, and is also a key supplier of the country’s liquefied natural gas. China is likely to be increasingly reliant on energy from the region in the coming years, as the country is projected to dramatically increase its energy consumption and only modestly raise its domestic production.

In this, diversity is important for China. The country has long maintained a somewhat balanced approach to its Gulf energy imports. Given the Gulf monarchies’ close ties to the United States, Beijing is concerned that Washington could put pressure on them to disrupt the flow of oil into China. This concern increases the perceived importance of Iran, which China sees as more resistant to US policy. At the same time, the current round of US sanctions on Iran underscores China’s reliance on the Arab side of the Gulf. Chinese oil imports from Saudi Arabia rose from 921,811 barrels per day in August 2018 to 1,802,788 in July 2019. Beijing is likely concerned about this level of dependence upon one energy source.

For China, another consideration is the United States’ central role in the protection of Middle Eastern shipping lanes crucial to Chinese oil imports. This vulnerability has become even more evident during the Sino-American trade war. With its main strategic rival able to threaten its energy security in this way, China has one more reason to expand its naval presence across the Indian Ocean – a process that could, in turn, lead to a larger Chinese security presence in the Middle East.

Construction, trade, and investment

The Gulf monarchies have been major sources of infrastructure construction contracts for Chinese firms, such as those for Qatar’s Lusail Stadium – the lead venue for the 2022 FIFA World Cup – and Saudi Arabia’s Yanbu Refinery and high-speed rail line that connects Jeddah with Mecca and Medina. Gulf Vision development programmes, which include major infrastructure projects, provide opportunities for further cooperation. Chinese firms have been active throughout the Middle East, often focusing on projects that lend themselves to the BRI goal of connectivity. Ports and industrial parks have been central to such cooperation, as they create an economic chain that links China to the Gulf, the Arabian Sea, the Red Sea, and the Mediterranean. Beijing first described this – which it calls the “industrial park – port interconnection, two-wheel and two-wing approach” – in summer 2018, predicting that it would be a major feature of China’s economic presence in the Middle East. The United Arab Emirates’ Khalifa Port, Oman’s Duqm Port, Saudi Arabia’s Jizan Port, and Egypt’s Port Said, and Djibouti’s Ain Sokhna Port all form part of this project. Chinese firms are also likely to play a major role in reconstruction projects in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen.

Meanwhile, Chinese trade with the Middle East has sharply increased in recent years, making the country the region’s largest trade partner. According to the International Monetary Fund, the volume of trade between China and the Gulf states was just under $197 billion in 2017. In 2016 China became the largest source of foreign investment in the Middle East. Projects linking China’s domestic development programmes to the BRI have also taken on greater importance in its bilateral relations across the Middle East.

Energy and space

The “3” in “China’s Arab Policy Paper” is especially interesting. Nuclear energy was once widely seen as a Western strength, but South Korea’s contract with the UAE to build the Barakah power plant demonstrates that the field has become more competitive. Chinese firms are also trying to enter this market in the Middle East. Saudi Arabia is an important potential customer, as it has long explored the possibility of commercial nuclear reactors as a source of domestic energy. Making initial inroads into the market, the China Nuclear Engineering Group Corporation signed a memorandum of understanding with a Saudi firm to desalinate seawater using gas-cooled nuclear reactors.

As part of the “digital Silk Road”, satellites are another priority for China in the Middle East. China’s BeiDou satellite navigation system has been used across the Middle East, as it has applications in telecommunications, maritime security, and precision agriculture. Telecommunication companies in Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE have all partnered with Huawei to build 5G networks.

Chinese firms have also been active in solar, wind, and hydroelectricity projects in the Middle East. This is especially true in the Gulf monarchies, where development projects such as Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 have prioritised the diversification of energy sources.

China’s partnership diplomacy

China has complemented its “1+2+3” plans for economic cooperation in the Middle East with strategic partnership diplomacy. Almost all of the strategic partnership agreements China has signed with countries in the Middle East and north Africa came about in the past decade (the one with Egypt, signed in 1999, is the sole exception). China has established comprehensive strategic partnerships with Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, as well as strategic partnerships with Djibouti, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, and Turkey. Coinciding with the expansion of the BRI, this flurry of diplomatic activity indicates that Chinese leaders increasingly perceive the Middle East as important to their political and strategic goals.

China’s relative lack of security commitments in the region – in comparison to the US – can create the impression that it does not take sides in regional rivalries or tip the scales in any of its partners’ favour. But this view misses the hierarchical nature of China’s partnerships, in which it privileges relations with comprehensive strategic partners above others. It also fails to account for China’s preference for stability in the Middle East; status quo-orientated states that are networked throughout the region offer more to Beijing than isolated states. Thus, when Xi visited the UAE in 2018 to upgrade China’s relationship with the country to the highest level, he demonstrated that it was a central pillar of China’s Middle East policy. In contrast, when Qatari Emir Hamdan Al Thani visited Beijing in January 2019, China did not upgrade the relationship but rather stated that it wanted to continue working with the framework established in 2014’s strategic partnership. This signalled China’s perception of Qatar as being less important than the UAE.

As China’s economic and diplomatic engagement with the Middle East continues to grow, it seems that security cooperation will soon follow – and there have been nascent moves in this direction. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) began visiting ports on the Arabian Peninsula as part of the international anti-piracy mission in the Gulf of Aden, giving Chinese naval officers the opportunity to develop relations with their Arab counterparts. China has also contributed UN peacekeepers to Lebanon since 2006. And there has been an increase in Chinese private security contractors’ work in the Middle East, as part of a response to deeper Chinese engagement with conflict-affected countries such as Iraq.

China’s arms sales to the Middle East have also increased in recent years – even if they are still minimal compared to those of Western states. Much of China’s success has been in filling orders that the US cannot because of congressional oversight, in areas such as armed drones and ballistic missile systems. Chinese companies can supply complete systems and accompanying services without political considerations. Nonetheless, Middle Eastern states generally prefer to purchase arms from the US, due to its advanced technology. However, China’s decision to only sell drones to countries such as Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE implies that it supports status quo powers. It has not sold advanced systems to non-state actors or revisionist states such as Iran (while the proliferation of armed drones is a real concern in the Middle East, it is likely to continue with or without Beijing’s help).

Another important security development has been the establishment of the PLAN Support Base in Djibouti, China’s first overseas facility of this kind. The move was a break from a long-standing Chinese practice of not constructing military installations in other countries. Given the dramatic growth of Chinese overseas interests, assets, and expatriates, Beijing needed to demonstrate that it had the capacity to protect these interests and did not need to rely on the US security umbrella. Substantial Chinese investments in Middle Eastern industrial parks and ports are commercial in nature for now, but may eventually have a military purpose. Host countries seem unlikely to allow this to happen in the near future, as many of them fear that it could compromise the security cooperation with the US they rely on. However, like the Djibouti base, China’s development of the Pakistani port of Gwadar has increased its maritime capacity in the region.

These features of Chinese economic, diplomatic, and security engagement with the Middle East form part of a deeper, broader, and more advanced strategy than might appear at first glance. China is changing gears, and leaders throughout the region are responsive to this.

Why is China’s approach to the Middle East changing?

The unipolar international order that emerged following the end of the cold war fundamentally shaped China’s approach to the Middle East. The US has been the dominant military power in the Middle East since Operation Desert Storm in 1990. With the US having established a regional security architecture that maintained the status quo it favoured, other foreign powers had to either work within that framework or challenge it. The US security umbrella helped China establish itself as a major economic and political power in the Middle East. Beijing has built its presence there through strategic hedging – steadily increasing in its economic engagement with the region, establishing relationships with all states there, steadfastly alienating no one, and avoiding policies that would challenge American interests in the region.

This approach has created a widespread perception of China as an opportunist that takes advantage of the US security umbrella to focus on its economic projects while providing little in the way of public goods. As the architecture of the BRI takes shape, this perception becomes increasingly difficult to sustain. China’s infrastructure projects complement domestic development programmes throughout the region, while its substantial investments, trade, and aid come at a time when the West suffers from Middle East fatigue. Rather than free-riding, China is providing public goods that can contribute to Middle Eastern development and stability.

More important, however, is Middle Eastern states’ perception of US retrenchment from the region. Many leaders in the Middle East felt that the election of Donald Trump as US president signalled a return to a robust American presence there – one that would support Gulf countries and Israel while boxing in challengers to the regional order, particularly Iran and its proxies.

Since then, the Trump administration’s regional policy – or lack thereof – has confounded expectations. In pulling out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the US applied pressure on Iran, but a lack of a clear policy to replace it has emboldened Tehran – as shown by the disruptions to shipping through the Strait of Hormuz in summer 2019. Trump followed up his threat to retaliate against Iran after the country shot down a US surveillance drone by calling off the planned strike, reinforcing the perception that the US commitment to stabilising the Gulf – which had remained steadfast since the announcement of the Carter Doctrine in 1981 – had diminished.

Beyond the Gulf, Trump’s announcement of a withdrawal from Syria has also signalled a decline in Washington’s presence, despite the overwhelming US military presence in the Middle East. Echoing the accusations that China was a free-rider made by his predecessor, Barack Obama, Trump tweeted: “China gets 91% of its Oil from the Straight [sic], Japan 62%, & many other countries likewise. So why are we protecting the shipping lanes for other countries (many years) for zero compensation. All of these countries should be protecting their own ships on what has always been a dangerous journey.”

In this context, China’s moves towards a greater role in Gulf security and trade could have significant implications. The country’s announcement in August 2019 that it might participate in a US-backed Gulf maritime security coalition could well signal the beginning of a deeper level of military engagement with the Middle East.

Despite its calls for an end to free-riding, the US has not been receptive to China’s expansion into the region. This is not especially surprising: the expansion of Chinese influence in the Middle East is a challenge to US dominance.

For now, the Trump administration is warning its Middle Eastern partners about the consequences of establishing deeper ties to China. The recent dispute over Shanghai International Port Group’s management of Haifa port is illustrative of this. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and then-national security adviser John Bolton both told Israeli officials to choose between Beijing and Washington. And US officials have strongly opposed Huawei’s introduction of 5G systems into Middle Eastern markets, citing potential security risks that could come with the company’s access to their networks such as invasive surveillance technology. The recent case of Turkey’s purchase of the Russian S-400 surface-to-air missile system, which US officials believe compromises the security of US-made F-35 aircraft, could resonate with Middle Eastern states.

Conclusion

In the face of inconsistent policies from the US and with an eye to a future with greater Chinese power and influence, leaders in the Middle East have been receptive to Chinese outreach so far. The BRI addresses their domestic development concerns and, at the same time, signals Beijing’s intention to become more invested in the region. This comes at a moment when Western countries, particularly the US, suffers from Middle East fatigue. At this stage, it is hard to determine whether this is merely a hedging strategy designed to diversify their extra-regional power partnerships or if it signals the beginning of a realignment that stretches across the Middle East to east Asia. It is clear, however, that China will be an engaged partner with a clearly articulated approach to building a stronger presence in the region.

China’s approach to the Middle East: Development before democracy

Degang Sun

Since Xi Jinping became president in 2013, the Chinese government has had strong aspirations to win greater support at home by transforming China from a regional power into a world power. With this mission in mind, Beijing launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI); established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Silk Road Fund; strengthened the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and the BRICS; and proactively participated in the G20, the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia, and other forums. These ambitious endeavours are designed to promote a new wave of globalisation in Asian, African, and European countries; increase their economic interdependence to enhance China’s global status abroad; and win the hearts and minds of the Chinese people.

For many years following the end of the cold war, China perceived the Middle East and north Africa (MENA) as a “chaotic and dangerous graveyard burying empires”, as Li Shaoxian of Ningxia University puts it. Compared to Asia, MENA was fragmented and insignificant due to its intense political instability. Yet, since 2013, China has regarded MENA as a crucial asset for promoting its status as a world power. Thus, Beijing’s position on MENA is shifting away from harvesting economic benefits while avoiding political entanglements and towards multidimensional engagement that covers all interests – albeit in a cautious way. In the coming years, China will incrementally increase its political and economic presence in MENA, with economic cooperation still the centrepiece of this effort.

China’s interests in MENA

In the new era, China – as a rising power – has a wide range of interests in the region. The most important of these is its interest in maintaining predictable great power relations, to enhance its political influence. China favours multipolarity rather than unipolarity in MENA. It seeks to expand its political influence vis-à-vis other great powers through its mediation of disputes across the region, particularly the Syrian war – which it has affected through its veto on the United Nations Security Council – and the disagreements that led to the 2015 Iran nuclear deal. In many ways, the relationship between China and MENA countries amounts to an attempt to hedge their bets against US predominance. Through strategic assertiveness and policy flexibility, Beijing wants to demonstrate to the Chinese people that, diplomatically, China is no longer a yes man but a respected world power – that it can maintain a strategic equilibrium with Europe, Russia, and the United States in the MENA and world arenas.

China’s second key interest relates to its principled support for state sovereignty and territorial integrity. China wants to promote this policy in MENA, largely through its position in the UN Security Council, to ensure wider international adherence to these norms. For instance, in July 2019, many Western countries criticised China for establishing re-education camps in Xinjiang, but Iran, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and other MENA countries publicly backed what Beijing calls its “deradicalisation efforts” in the autonomous region – in what appeared to be a staunch show of support for China’s sovereignty.

China’s third interest relates to its commercial ties, which include energy, trade, and investment. There is a convergence of BRI projects in MENA, which sits at the crossroads of Africa, Asia, and Europe. According to China’s General Administration of Customs, in 2018, China imported around 462m tonnes of oil (almost half of which came from MENA), and was the largest trading partner of 11 MENA countries, including Iran and ten Arab states. By mid-2019, China had signed agreements with 21 MENA countries (including 18 Arab states) on joint BRI projects. China’s growing ambitions to incorporate MENA into the BRI, for both economic and wider strategic reasons, has led it to significantly increase its engagement with the region.

Finally, China has diplomatic interests in MENA. In 2016, when a territorial dispute in the South China Sea intensified, the Arab League supported China through the Doha Declaration. The organisation sided with Beijing’s position that the conflicting parties should settle their disputes bilaterally, without the involvement of foreign states or international organisations such as the Permanent Court of Arbitration. Support from 22 Arab countries mitigated China’s isolation and embarrassment in south-east Asia after the court ruled against it on the dispute.

To safeguard all these interests, China has relied on four measures: mediation diplomacy; the expansion of its political partnerships with pivotal MENA countries; the deployment of peacekeepers; and deepening economic cooperation.

Mediation diplomacy

Prolonged wars in MENA have provided Beijing with a significant opportunity to enhance its status as a world power through conflict resolution. In October 2017, Xi emphasised that “China is increasingly approaching the centre of the world stage” and, therefore, had a duty and a desire to make a greater contribution to MENA conflict resolution – and to create public security goods in the region through bilateral and multilateral cooperation. China has now nominated special envoys for African affairs (Sudan), the Middle East peace process (Israel-Palestine), the Afghan conflict, and the Syrian war. Chinese special envoys are generally more pragmatic and patient than their European and US counterparts, seeking incremental solutions to thorny problems – albeit through responses that can be passive and inefficient at times.

China’s involvement in mediation in MENA often takes the form of a cautious approach to conflict resolution in which it becomes engaged with the process but does not play a decisive role. Beijing chooses to participate rather dominate; to follow rather than lead; to put forward constructive ideas rather than set agendas; and to pursue de-escalation rather than all-out resolution in complicated wars.

China’s involvement in these mediation efforts is selective, largely dependent on its interests and capabilities. Due to its still-limited influence, China only acts as a mediator in four broad ways. The first of these is multifaceted interventions in places such as Sudan and South Sudan, countries in which China’s huge investments have given it significant political influence. The second is proactive engagement with disputes such as those around the Iranian nuclear programme and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The third is limited intercession such as that in the Libyan civil war, the Syrian conflict, the Yemeni war, the Saudi-Iranian dispute, and the Gulf states’ blockade of Qatar – all situations in which China has limited influence. The fourth way is indirect participation such as that through the UN on the Somali crisis; the Western Sahara issue; Iran’s maritime disputes with the United Kingdom and the US; the sectarian conflicts among Sunni, Shi’ites, and Maronites in Lebanon; and military campaigns against the Islamic State group, al-Qaeda, and their affiliates. Because it lacks substantial interest in or influence on the parties, China’s involvement in these cases is minimal – merely a gesture of goodwill.

Strategic partnerships

China’s regional partnerships differ from those of the Western alliance: the former seeks flexible political cooperation based on informal political bonds while the latter often targets external enemies based on defence treaties. Since 2013, China has gradually constructed a multidimensional global partnership network that involves great powers, neighbouring countries, and developing countries, as well as regional organisations such as the African Union and the Arab League. China sees these 90 layered partnerships as interlinked and mutually reinforcing.

China’s relationships in MENA are a crucial component of its global partnership network. These 15 relationships – spread across the eastern Mediterranean, the Gulf, the Maghreb, and the Red Sea – fall into four broad categories in line with their importance. The first category comprises comprehensive strategic partnerships with Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The second includes a comprehensive innovation partnership with Israel and a strategic cooperative relationship with Turkey (the latter being inferior to a strategic partnership, while a strategic partnership is inferior to a comprehensive strategic partnership). The third covers strategic partnerships with several mid-sized countries: Iraq, Morocco, and Sudan. The fourth comprises strategic partnerships with the smaller states: Djibouti, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar. The Gulf is the focal point of China’s strategic partnerships, because there are substantial Chinese interests there.

Governments in MENA generally welcome partnerships with Beijing because, they claim, it treats them as equals rather than junior partners or colonial proxies. Combined with its policy of non-interference in others’ internal affairs, non-alignment, and refusal to engage in proxy wars, China has stayed on good terms with all conflicting parties – including Iran and Saudi Arabia, Arab countries and Israel, and Algeria and Morocco – because its partnerships do not harm or provoke third parties.

Peacekeeping

Although China adheres to what it calls its “zero enemies” policy in MENA, it has cautiously engaged with the region militarily to safeguard its interests. As the Trump administration begins to disengage from MENA, China is finding it harder to play a low-key role in the region.

China has few military assets in MENA. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, the US supplied 54 percent of arms transfers to the region between 2014 and 2018, while Russia provided 9.6 percent, and France 8.6 percent. In comparison, China’s share was minimal – less than 5 percent. However, Chinese arms sales to MENA have increased in recent years. Its drones are manufactured in Saudi Arabia and deployed to Egypt and Iraq for counter-terrorism purposes. According to China’s Ministry of National Defence, the country has deployed around 1,000 troops to Obock logistics base, in Djibouti, for anti-piracy missions. By July 2019, China had dispatched 32 convoy flotillas to Somali and adjacent waters to provide security in the Red Sea and the Arabian Sea.

Despite this light, independent military footprint in MENA, China’s peacekeeping contingent in the region is, according to the UN, the largest of any permanent member of the Security Council. In 2015 Xi declared that China would donate $1 billion to the UN’s Peace and Development Trust Fund, and that it would train 2,000 peacekeepers for other UN member states. As of April 2018, China had contributed more than 1,800 soldiers and police officers to UN peacekeeping missions in or near MENA: Western Sahara (MINURSO, ten personnel), Darfur in Sudan (UNAMID, 371 personnel), Lebanon (UNIFIL, 418 personnel), South Sudan (UNMISS, 1,056 personnel), and Israel-Palestine (UNSCO, five personnel).

In addition, the Chinese military has engaged in operations approved by the UN Security Council. For example, in 2013, Chinese navy vessels escorted UN ships carrying chemical weapons out of Syria for destruction in Cyprus. China has often deployed military forces to support the evacuation of Chinese citizens from MENA countries such as Lebanon in 2006, Libya in 2011, and Yemen in 2015.

Finally, Chinese investors do not simply rely on Western private security contractors and local security forces: China dispatches private security contractors to war-torn countries and regions to protect Chinese expatriates and Chinese-funded infrastructure. The “Snow Leopard” commando unit (which is affiliated with China’s armed police), Tianjiao Tewei (GSA), and Huaxing Zhong’An are just a few of the Chinese firms involved in the private security market in MENA.

China’s developmental peace model

As the largest foreign investor in MENA, China regards the region as a potential market rather than an important security environment. According to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, in 2018, China’s trade with 22 Arab countries reached $244.3 billion; Sino-Iranian trade nearly $36 billion; Sino-Israeli trade $13.9 billion; and Sino-Turkish trade $21.6 billion. China signed investment contracts worth $33 billion with Arab countries in 2017. Today, there are more than one million Chinese expatriates in MENA for business or study, or on pilgrimages. China has engaged in post-war reconstruction projects in Iraq in the name of development and will continue to pursue business opportunities in Lebanon, Libya, Sudan, and Syria.

China has pushed the concept of developmental peace – in contrast to the Western concept of democratic peace – in MENA, arguing that the root cause of regional insecurity is economic stagnation, high unemployment, poor infrastructure, rapid population growth, and brain drain rather than a democracy deficit. Therefore, while Moscow and Western capitals play an important role in the conflicts in Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Palestine, Syria, and Yemen, Beijing may become deeply involved in these countries after they move towards post-war reconstruction.

China’s argument that, for all MENA countries, development is more important than democracy is reflected in its development-orientated approach to governance. Beijing believes that the international community should provide badly needed economic assistance to MENA countries instead of exporting ill-fitting democracy to them. Despite having different methods, China and Western powers could have similar end goals in the region and could find ways to converge on them: their immediate aim is development, which will lay a foundation for the West’s long-term goal of establishing democracy in MENA.

Chinese development aid to war-torn MENA countries is in proportion to Beijing’s general influence there. It has provided $100m to the UN peacekeeping mission in Somalia since 2015. Since 2018, China has supplied approximately $85m to humanitarian reconstruction in Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and Yemen; $14m in humanitarian aid to Palestine; $140m to Arab countries for capacity building; and $42m to Arab countries for training law-enforcement officers. Beijing argues that, through economic and social reconstruction, MENA governments can eradicate violence and radicalisation. China’s reform and opening-up experience taught it that economic and social development is an absolute necessity for MENA countries in transition.

Conclusion

Beijing has a negative view of the Western practices of alliance politics, spheres of influence, and economic sanctions. It is wary of the concept of the responsibility to protect, opposes regime change, and dismisses the argument that some governments in war-torn MENA countries are evil or are troublemakers. Beijing stresses that all MENA states are partners in a dialogue on inclusive and comprehensive solutions to conflicts. China attempts to burnish its world power status by upholding these standards.

As a rising power, China engages with MENA in experimental and preliminary ways that are devoid of a clear strategy. The ruling party aims to increase its popularity at home rather than seek a geopolitical rivalry with the US in MENA. It does so by maintaining stable great power relations and expanding its commercial interests across MENA. Thus, China avoids direct contests for control with established powers such as the European Union, Russia, and the US. China and Russia have jointly vetoed seven draft UN Security Council resolutions on the Syrian war, but Beijing has refrained from forging a full alliance with Moscow. Unlike Moscow, Beijing does not establish military bases in conflict zones. Nor does it seek to establish a sphere of influence in MENA.

China feels comfortable with its independent policy in MENA. It believes that other powers should abandon what it sees as their cold war mentality to establish a new security order based on burden-sharing and public goods, thereby promoting sustainable peace and development. Since it seeks partnerships with other powers, China is likely to strengthen its cooperation with the EU in seeking to de-escalate conflicts in Israel-Palestine, Libya, Syria, and Yemen, and to address the Iranian nuclear issue. Both China and the EU emphasise the need to stick to the Iran nuclear deal; support the two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict; back a political resolution, and oppose any power’s attempt to dominate security affairs, in the Syrian war; and underscore the central role they believe the UN should play in resolving the Libyan and Yemeni conflicts. For years to come, China’s BRI and European powers’ economic investments will provide the kind of development assistance to MENA countries that is conducive to regional peace and stability. The two sides will form a partnership to solve MENA refugee issues.

Because the established powers have lost some of their interest in MENA affairs, China does not think it will be able to maintain its low-key approach to the region for much longer. Thus, it will explore channels to defend its commercial interest and construct congenial and cooperative great power relationships in MENA. China’s position on the region may shift a great deal more in the years to come.

The GCC’s China policy: Hedging against uncertainty

Naser Al-Tamimi

The six states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates – have diversified their foreign policies in the past two decades by paying more attention to east Asia. As part of this Look East policy, they have focused on China, Japan, South Korea, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

This shift has occurred largely due to two main factors. The first is that China’s spectacular economic rise over the last three decades has led to a sharp increase in the country’s energy demand. In the process, GCC countries have become the centre of gravity for Chinese economic activity in the Middle East and north Africa (MENA). Gulf states are intent on further strengthening these economic ties.

The second factor reflects GCC states’ increasing uncertainty about the trajectory of their relations with the United States – particularly given the rise in tension between Washington and Riyadh after 9/11, as well as the Obama administration’s pivot to Asia and its response to the Arab uprisings. While the US-GCC relationship has significantly improved under President Donald Trump, the unwritten “oil for security” architecture on which it is based has become increasingly complex and, at times, contradictory. The US shale boom may eventually give America the chance to end its dependence on oil imports from the Gulf.

At the regional level, Gulf Arab states – particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE – are concerned that a new nuclear agreement between the US and Iran will cause Tehran to become more assertive. Another issue that worries them is Washington’s failure to halt Tehran’s nuclear programme. Their fears that the US will disengage from, or even abandon, the Middle East are real – as much so under Trump as under his predecessor.

In this context, GCC countries have an interest in avoiding excessive reliance on the US. Thus, Gulf Arab states – particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE – are working along parallel routes: strengthening their independent military capabilities and aggressively diversifying their economic and military ties with key external players, such as China. In the long run, this could push some Gulf Arab states to strengthen their military and security ties with China or host Chinese military facilities, including naval bases.

An economic superpower

As an economic superpower, China has an ever more strategically important role for Gulf states. The scope of China’s interests in the Gulf has grown in recent years – from a narrow focus on the hydrocarbons trade to wide-ranging investments in energy, industry, finance, transport, communications, and other technology. China has also become an increasingly important stakeholder in the GCC’s economic diversification programmes. Bilateral trade between China and GCC states doubled to almost $163 billion in the decade to 2018 – and is projected to grow further in the coming years. China is now the GCC’s top economic partner and the largest trading partner of Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

Chinese contractors nowoutperform their South Korean counterparts in the Gulf. Analysis of MEED Projects data shows that Chinese firms have conducted work worth $38 billion there since the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. This is almost double the amount they carried out during 2007-2012. Last year, the region was the second-largest recipient of investment through Chinese construction projects worldwide. In 2018 nearly two-thirds of Chinese investment in MENA went to GCC countries.

Already the world’s largest energy consumer, China will be increasingly dependent on oil and gas imports as its economy grows in the coming decades. In 2018 almost 30 percent of China’s oil imports – or 2.9m barrels per day – came from GCC countries (with more than half of this coming from Saudi Arabia alone).

Therefore, the two most powerful GCC states – Saudi Arabia and the UAE – will remain the cornerstone of China’s economic policy on the Middle East. The UAE’s partnership with the Chinese is mainly economic in nature, not least because the country aspires to become the region’s main gateway for the BRI. An estimated 60 percent of China’s European and African trade passes through the UAE.

Riyadh’s economic relationship with Beijing is anchored in energy. Sino-Saudi energy relations have recently undergonedevelopments that could have important long-term repercussions. Firstly, Saudi Arabia is set to expand its share of the Chinese energy market for the first time since 2012. This is due to Saudi Aramco’s new agreements with Chinese companies to increase the volume of its crude supply to China. The deals have caused China to become the largest market for Saudi oil exports, surpassing the US and Japan for the first time in history. Saudi Arabia could soon overtake Russia to reclaim the title of the biggest crude supplier to China.

Gulf and Chinese economic interests are also converging across a wider geographical area. Riyadh hopes that Beijing’s increasing focus on the Red Sea region will involve greater attempts to shape the future of maritime trade there and in the western Indian Ocean. This Chinese expansion coincides with the ambitious plans of Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia to build new ports or increase the capacity of existing ones in the region. These plans may partly explain why the UAE seeks to aggressively invest in the BRI – especially in the Horn of Africa – and thereby maintain its leading economic position in the region. Although it is keen to attract Chinese investment, the UAE is also wary of the expansion of Chinese companies in the ports of the region, which could threaten the status of Dubai as a regional trade centre.

Meanwhile, Gulf Arab states want to invest in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a centrepiece of the BRI. For example, Saudi Arabia has offered Pakistan around $16 billion in loans and investments related to the project. This includes a $10 billion investment in an oil refinery and petrochemicals complex in the deep-water port in Gwadar, a Pakistani city on the coast of the Arabian Sea. Although there are significant political aspects to this support, these projects also align with Saudi Aramco’s ambitious plans to diversify its energy portfolio and expand into Chinese, Indian, and other Asian markets – which are at the centre of global growth in energy demand.

China’s regional strategy

Gulf states are aware that China’s economic growth could eventually translate into increased military power in MENA, allowing it to adopt more assertive policies in the region in pursuit of its strategic goals. Despite its efforts to diversify its sources of oil in the last decade, China remains dependent on the Middle East and Africa for around two-thirds of its total imports. Thus, Beijing continues to rely on sea lines of communication such as Bab el-Mandeb, the South China Sea, the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Malacca, and the Suez Canal for most of its trade and energy imports. Additionally, projects associated with post-conflict reconstruction in other MENA countries – such as Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen – could eventually cost hundreds of billions of dollars. Chinese enterprises have an opportunity to win a large share of these contracts.

As China’s capabilities grow and its dependence on oil from MENA rises, Beijing is likely to use its military to advance and protect these vital interests in the coming decades. Gulf states cautiously welcome the prospect of a growing Chinese role in the region – although they want to ensure that China remains invested in protecting their interests. They would like China to eventually offer them a possible alternative security arrangement to that provided by the US – either individually or through a multilateral initiative.

China’s growing economic and military power, along with its permanent seat on the UN Security Council, ensures that its global influence will only increase over time. This is why GCC states view China as an important source of political support – particularly when they are embarking on diversification programmes and selective economic reforms, while resisting Western pressure on issues such as human rights and democratisation. China’s silence on the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Saudi Arabia’s Istanbul consulate last year reinforced Gulf states’ belief that their worldview is more closely aligned with Beijing’s than with those of their long-standing Western partners.

China backed the collective security concept Russia recently proposed for the Gulf, which calls for a “universal and comprehensive” security system that “should be based on respect for the interests of all regional and other parties involved, in all spheres of security, including its military, economic and energy dimensions”. China, Gulf states, and Russia share a broad commitment to the principles of state sovereignty and non-interference in other countries’ domestic affairs, and to economic development rather than democratic reform.

China has largely refrained from direct involvement in disputes in MENA and has established good ties with all countries in the region. However, Gulf Arab states are concerned about China’s policy on Iran, particularly the military relationship between the two. Yet Beijing has taken a cautious approach to Tehran, despite its support for the Iran nuclear deal. All economic indicators show that China has not invested heavily in Iran – despite Tehran’s claims to the contrary – and that most Chinese military manufacturers are unwilling to provide technology transfers to Iranian companies (as has been the case with Pakistani firms).

More broadly, if Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia lose faith in the US to defend their interests – perhaps due to Washington’s failure to halt the Iranian nuclear programme – they will be more likely to start their own nuclear programmes or acquire advanced ballistic missiles. While there is no evidence that Saudi Arabia is pursuing this option, China and Pakistan are among the countries that it would likely cooperate with in such an effort. The US government has reportedly acquired intelligence that Riyadh has been developing its ballistic missile programme with the help of Beijing. Saudi Arabia bought ballistic missiles from China in the 1980s and there has since been speculation that Riyadh purchased improved versions of these weapons.

Nonetheless, military cooperation between China and Gulf countries is still in its infancy. Beijing has a limited capacity to compete with Western arms suppliers. Indeed, Chinese security ties with GCC countries are confined to joint exercises, counter-terrorism cooperation, sales of some weapon systems, and joint production of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Between 2013 and 2017, China sold military equipment worth $10 billion – including armed UAVs, precision-guided rockets, and ballistic-missile systems – to Middle Eastern countries. Most of the purchases were made by Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Yet this is a negligible amount in comparison to MENA countries’ huge arms deals with US firms. Moreover, many Chinese weapons are less technologically advanced than those of Western military powers.

A delicate balancing act

While Gulf Arab states seek the economic and political benefits of an increased Chinese role in MENA, they know that they need to balance this with the shorter-term imperative of not alienating the US. Decision-makers in GCC states do not believe that China has the military and logistical capabilities (and, possibly, the political will) to provide a credible alternative to the US security umbrella in the Gulf. The US has deployed tens of thousands of troops to the region and maintained bases in every GCC country except Saudi Arabia, as well as in Afghanistan, Iraq, Jordan, Turkey, and Syria. From the perspective of Gulf Arab states, the security umbrella provided by the US military will, despite the increasing uncertainty in US-GCC relations, remain crucial for maintaining peace and stability within the Gulf and in defending their wider regional interests for years to come.

Indeed, GCC countries’ strong military ties with the US may limit their support for an increased Chinese military presence in the Middle East – at least in the short term. Oman perhaps provides an example of this. Although China is the largest market for Omani oil exports, and Chinese companies are widely expected to be the biggest investors in the Omani port of Duqm, Muscat has granted the US military access to facilities in both Duqm and Salalah. Additionally, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are among the few countries to have purchased Terminal High Altitude Area Defense and Patriot missile systems from the US. The bottom line is that Gulf Arab states do not want to damage their military ties with the US by engaging in too much military cooperation with China (or Russia).

The US will likely pressure its MENA allies to limit their engagement with China, particularly in military affairs. Indeed, some Gulf leaders fear that the deterioration of the US-China relationship could put them in the awkward position of having to choose sides – as they may have to do in the dispute over Chinese technology giant Huawei (which could have negative economic consequences for the Middle East). Michael Mulroy, the top Pentagon official for the region, recently warned that China’s efforts to gain influence in the Middle East could undermine defence cooperation between the US and its Gulf allies.

Still, with China’s rise likely to continue in the long term, there remains a possibility of a more comprehensive geopolitical shift across the Middle East. China’s persistent efforts to secure energy resources and build strategic partnerships will remain a source of direct competition with the US. Gulf Arab states are likely to seriously consider multiple politico-security arrangements, particularly if the US partially withdraws from the Middle East or the tension between Washington and GCC capitals intensifies. Of course, this will also force Beijing to make some hard choices. If China wants to increase its influence in MENA, it will have to involve itself in the messy geopolitics of the region and be more assertive in its use of economic and other strategic assets there.

About the authors

Camille Lons is a research associate at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, based in the Middle East office in Bahrain. She covers political and security developments in the Gulf region, with a specific focus on Gulf countries’ economic and political relations with Asian powers and the Horn of Africa. She previously worked as the coordinator of ECFR’s MENA programme.

Jonathan Fulton is an assistant professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi. He is the author of China’s Relations with the Gulf Monarchies (Routledge, 2018).

Degang Sun is a professor at the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University. He was deputy director of the Middle East Studies Institute at Shanghai International Studies University, and the editor-in-chief of the Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies. He was a visiting scholar at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University (2018-2019), and a senior associate member of St Antony’s College of Oxford University, as well as an academic visitor to the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies (2012-2013), Denver University (2007-2008), and Hong Kong University (2004-2005). His research focuses on Middle Eastern politics and international relations, great powers’ strategies in the Middle East, and China’s Middle East diplomacy. He can be reached at [email protected].

Naser Al-Tamimi is a UK-based political economist focused on the Middle East, with research interests in energy and Arab–Asian relations. He received his PhD in international relations from Durham University in the United Kingdom, where his thesis focused on China’s relations with Saudi Arabia. He has written widely on matters concerning Saudi Arabia, the Gulf, and the Middle East for both academic and popular publications. He is the author of China-Saudi Arabia Relations, 1990-2012: Marriage of Convenience or Strategic Alliance? (Routledge, 2014).

Acknowledgements

Naser Al-Tamimi would like to thank Julien Barnes-Dacey and Camille Lons for their helpful comments.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.